Treating Seasonal Affective Disorder

How to Face Winter with a Smile

Getting blue as the days grow shorter? Sleeping a lot during winter but feeling even more tired? Turning to bread and pasta for comfort during cold weather?

If these symptoms describe you or someone you know, it may be due to a major depressive disorder with a seasonal pattern, better known as seasonal affective disorder (SAD).

For people who struggle with this condition, turning to medication probably isn’t the best course of action. Here’s why: A comparative analysis of prior research trials found that

anti-depressants were no more effective than a placebo, except for the most severely depressed subjects. Subsequent broad-based studies show that alternative approaches to the

treatment of depression – including

psychotherapy and regular exercise – are just as effective as psychiatric medication, especially in the long run.

Instead of turning to drugs, you may be able to take a series of active and independent steps to improve your condition yourself. Rather than viewing SAD as a

disease state that requires medical intervention, look at it as an extreme version of a very common response to the shorter days of winter.

SAD as a Spectrum Disorder

When it was first identified and discussed in the early 1980s, researchers considered SAD a separate and distinct “mood disorder,” and it was incorporated as such into

the American Psychological Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual III-R (1987) (DSM). In later versions of the DSM, however, SAD was re-classified as a

sub-type of depression whose onset varies predictably over the course of the year – usually during the fall and winter months and less rarely in spring. It is sometimes

referred to as winter depression, the winter blues, or seasonal depression.

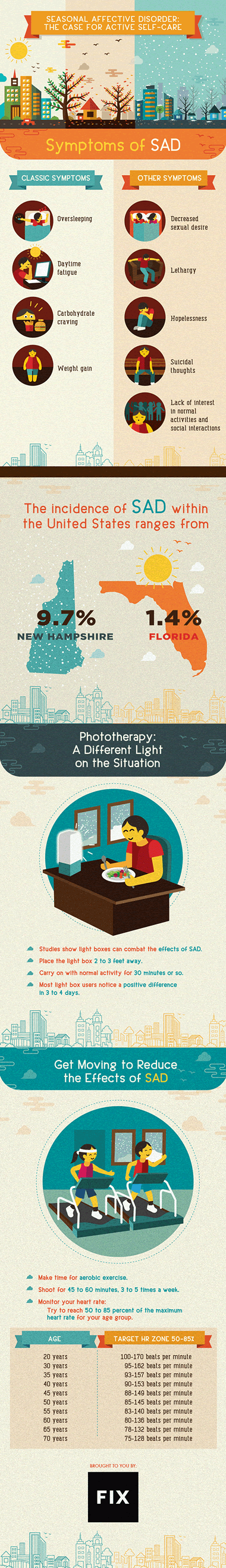

The classic symptoms of SAD include oversleeping, daytime fatigue, carbohydrate craving, and weight gain. Some people may also experience other

symptoms of depression including decreased sexual desire, lethargy, hopelessness, suicidal thoughts, and lack of interest in normal activities

or social interactions. Most importantly, and unlike Major Depressive Disorder, the symptoms of SAD come and go with the change in seasons.

Many of us experience a lower mood and energy level during the winter when days are shorter and temperatures get colder, but a few of us feel

especially low and lethargic. If the winter skies remain cloudy for days on end, everyone’s mood may darken and irritability rise, but for

some people, depression will take hold. In other words, there is a spectrum of possible responses to seasonal changes in light and weather.

SAD represents one end of that spectrum.

DSM5, the most recent version of the APA’s diagnosis manual, recognizes this spectrum by including mild, moderate, and severe variations in

SAD, as well as a “subsyndromal” designation when symptoms fall short of the diagnostic threshold. I would go further and argue that changes

in the weather and the seasons affect everyone’s moods to a degree, with some people more severely influenced than others.

Viewing SAD from this perspective rescues it from the disease model that pervades modern psychiatry. While the medicalization of mental illness has gone a long way toward relieving the shame that used to surround depression, it encourages a passive attitude toward an individual’s

condition: You have a chemical imbalance in your brain, and all you need do is take this drug to rectify it. Because people who struggle with

depression often lack energy and motivation, taking a pill as the sole solution is an understandably welcome prospect.

But selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as Zoloft and Lexapro, the most commonly prescribed anti-depressants, may have side

effects including weight gain, loss of sexual desire, and even thoughts of suicide. More seriously, evidence that SSRIs cause long-term

neurological damage continues to grow. With mounting doubts about the ongoing effectiveness of these drugs – and concerns about the physical harm they may cause – it makes sense to consider alternative treatments for depression.

If you struggle with SAD, you have several excellent alternatives to psychiatric medication.

Light Therapy

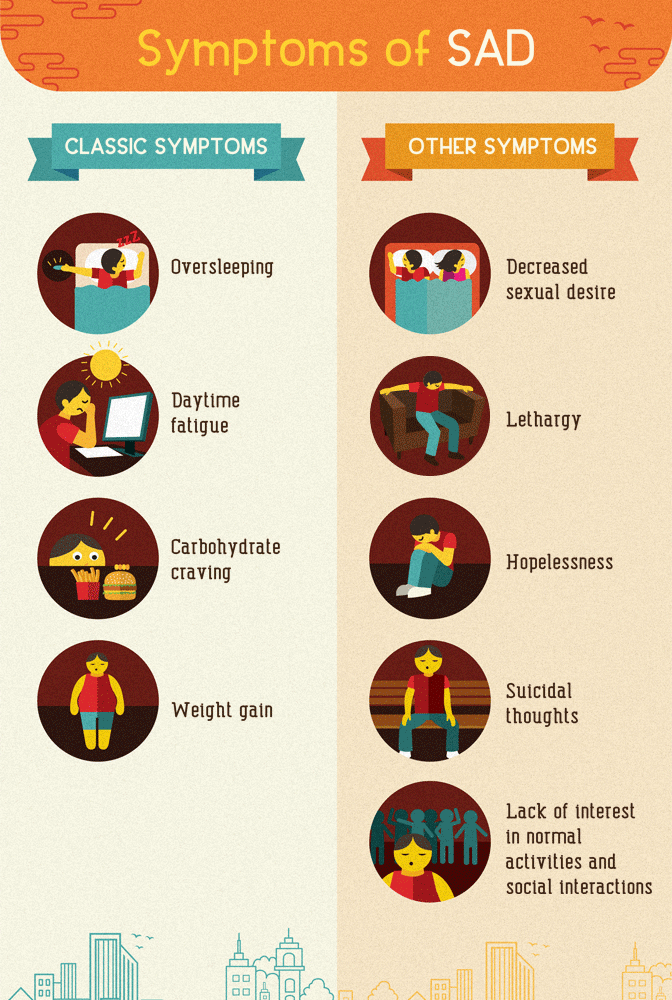

Given the correlation between waning daylight during winter months and the onset of depressive symptoms, it comes as no surprise

that SAD occurs more commonly in states or countries further away from the equator, where winter days are shorter. SAD also occurs more

commonly in the Nordic region of Europe than in sunnier and warmer countries to the south.

Even in northern climates, simply getting outside during the day helps to alleviate the symptoms of SAD. Exposure to sunlight – perhaps by taking a

daily walk or eating lunch in the local park – has helped many people who suffer from winter depression. Because harsh weather or heavy rainfall may preclude

this “natural” approach, indoor devices (such as light boxes) simulate the effects of direct sunlight.

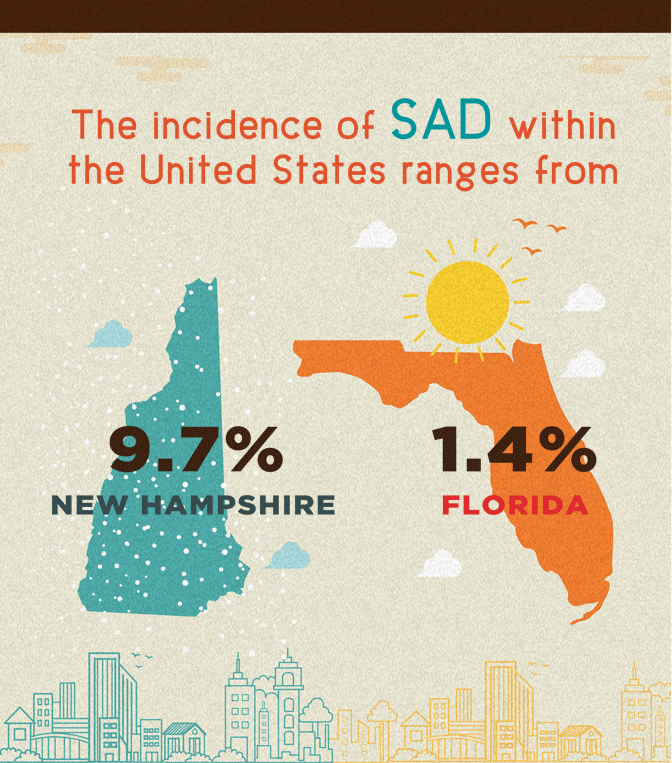

Phototherapy refers to the use of light-emitting devices to offset the effects of decreased daylight during winter. The recommended course of treatment

is 30 minutes of fluorescent soft-white light at 10,000 lux a day. One lux represents a standardized unit of illumination (normal light bulbs emit

only 250 to 500 lux while exposure to direct sunlight provides as much as 100,000 lux). Light boxes vary in power, so using one that emits less than

10,000 lux may require exposure for more than 30 minutes.

Light boxes come in various shapes and sizes, but most common one is about as as tall and as wide as a sheet of printer paper.

Users place the box on a desk or table, then sit about two to three feet away. While it’s best to face the light box, it’s not necessary

to look directly into the light. Most people read, eat, or do paperwork in order to pass the time. While 30 minutes of exposure is average,

individuals may need either more or less time to achieve satisfactory results.

In controlled studies, about 75 percent of participants reported relief from their symptoms within three to four days. By contrast, anti-depressants typically need four to six weeks to take effect.

Some people respond better to phototherapy during the morning hours, others during the evening. Center for Environmental Therapeutics has a set of questionnaires that will help you determine the most effective time to use a light box.

There are various theories about the influence of light on depressive symptoms. Some focus on levels of serotonin

(a neurotransmitter or chemical messenger for the central nervous system) and others on melatonin (a hormone involved in the regulation of sleep cycles),

but there is no conclusive evidence to support any of them. While we may not know exactly how light therapy works, its effectiveness and ease of use are clear.

Phototherapy should be an integral, daily part of the SAD sufferer’s self-care regimen.

Psychotherapy

Even if symptoms improve with light therapy, people experiencing SAD may still need to address the legacy of having felt lethargic, withdrawn, and depressed

for several winters. Not surprisingly, relationship breakdowns and career problems are common among SAD sufferers. Psychotherapy or counseling may help individuals

confront and resolve these issues. Several options are available, and according to recent studies, they are all about equally affective.

Cognitive Therapy

Cognitive therapists believe the particular nature of our thoughts will determine the emotions we feel. They help their clients learn to identify certain

common patterns of negative thinking, or “cognitive distortions,” and then convert those negative thought patterns into more positive ones. In the process, a client’s mood can improve.

Behavioral Therapy

As its name suggests, this type of psychotherapy focuses on changing undesired behaviors. It uses the principles of classical and operant conditioning to

encourage behaviors that are desired while discouraging those that promote depressive feelings. Behavioral therapy tends to be short-term and highly focused;

it does not address unresolved (and usually unconscious) issues that may underlie the depression.

These first two treatment modes are often combined and jointly referred to as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

Interpersonal Therapy

This form of treatment focuses on the client’s interactions with family, friends, co-workers, and other important people encountered on a

day-to-day basis. Its primary goal is to improve communication skills and increase self-esteem within a short time period – usually three to

four months. Interpersonal therapy appears to be effective for addressing the social isolation and relationship conflicts that are so often a

component of SAD.

Psychodynamic Therapy

Based on the assumption that SAD is compounded by unresolved, unconscious conflicts rooted in childhood, this type of therapy aims

to help the client understand and better cope with depressed feelings by talking about those past experiences. Psychodynamic therapy may

last for several weeks but typically continues for months or even years.

Health insurance usually covers the type of short-term, goal-directed therapy described above. With the passage of the Mental Health Parity

and Addiction Equality Act in 2008 and the Affordable Care Act in 2010, coverage for mental health issues is now a standard part of most health

insurance policies. Even if you aren’t covered by such a policy, most communities have free or “sliding scale” clinics where fees are based upon

a client’s ability to pay. Light boxes are highly effective in alleviating many of the symptoms of SAD, but getting support from a trained

professional may help you to make a full recovery.

Exercise

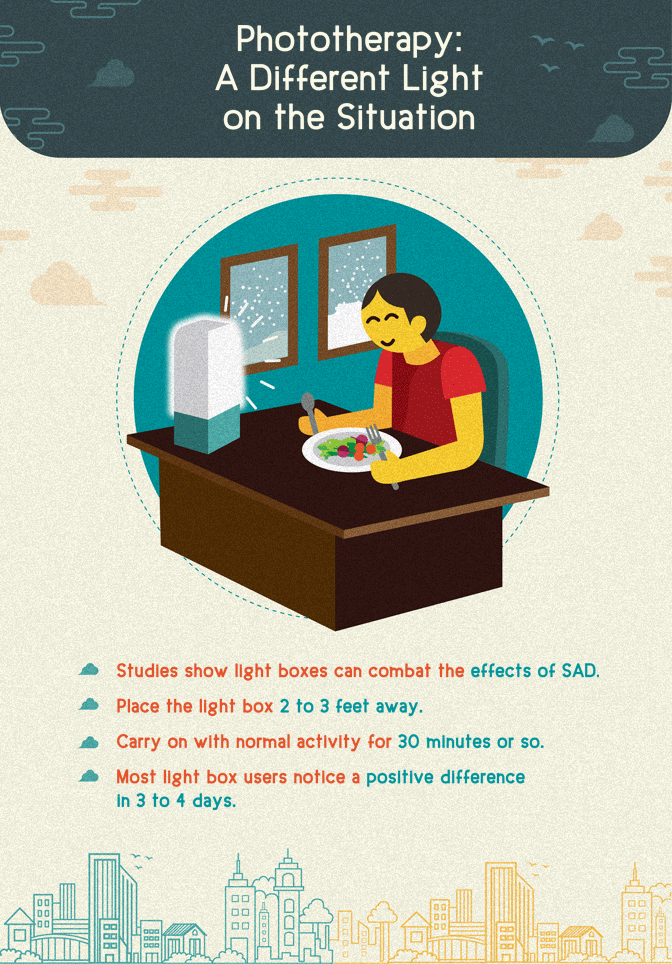

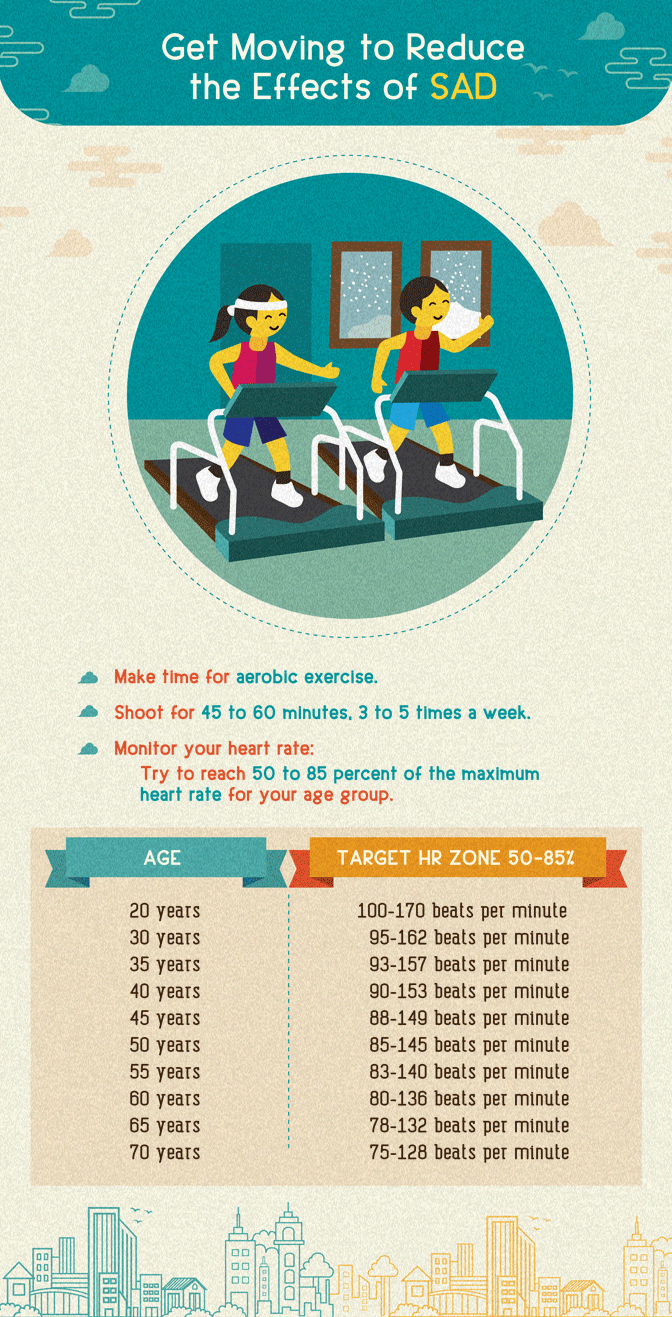

Aerobic exercise – and, to a slightly lesser degree, strength training – has been shown to

alleviate symptoms of depression as effectively as medication, and its benefits tend to

last longer. A consistent exercise regimen has general health benefits as well, and can build self-esteem. A self-care plan to address SAD should include regular exercise.

The effectiveness of exercise for alleviating depressive symptoms has been recognized for many years, but based on recent studies the recommendations have grown more specific.

Research suggests working out three to five times a week for 45 to 60 minutes each session. During aerobic exercise, shoot for 50 to 85 percent of the maximum heart rate for

your age group. (Guidelines for how to determine and reach this maximum are provided by the American Heart Association.)

To help adhere to an exercise program, choose an activity you enjoy. Seek encouragement from a therapist or counselor. Find an exercise partner for mutual support.

In extreme cases of SAD, it may be necessary to combine short-term use of anti-depressants with a self-care program.

But for most people who struggle with seasonal depression (or even those of us who merely experience reduced energy and

darker moods when the days grow short), resorting to medication is unnecessary. Increased exposure to natural or artificial light,

regular cardiovascular exercise, and psychotherapy when needed can make the winter feel a lot less gloomy.

Embed the article on your site