Easy Crop Rotation For Your Garden

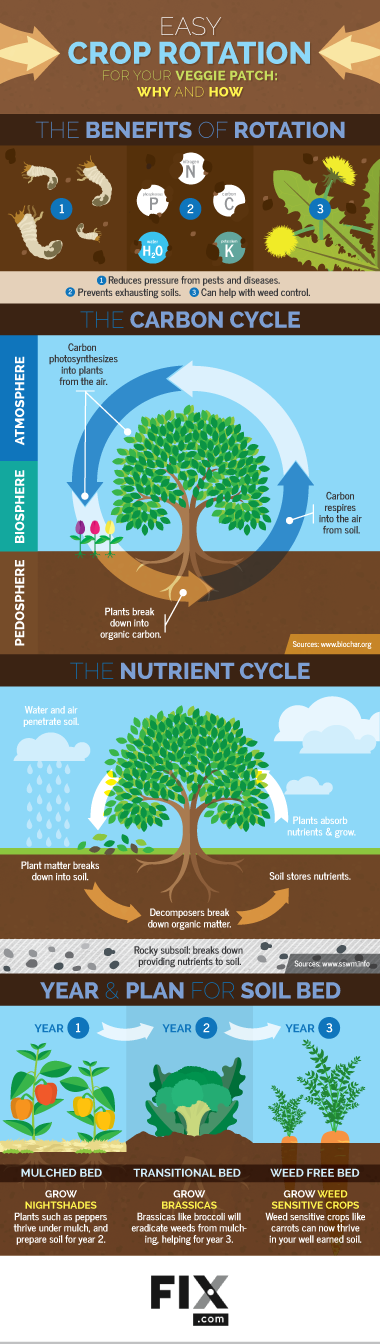

Rotating crops can help break pest and disease cycles, improve soil health, and even reduce maintenance while increasing yields. But the thought of rotational planting can be daunting. This article explains why crop rotation is important and sets out a simple three-year rotation for an organic vegetable garden.

Why Rotate?

Crop rotation is perhaps the most fundamental practice of any grower working any plot of land anywhere in the world. The benefits are well known and apply to both organic and conventional (chemical) management programs. Crop rotation is essentially free because the only ‘cost’ involved is the time spent planning.

Traditionally, rotation has been used to break pest and disease cycles and as a way to preserve soils even while planting the same type of plant over and over in the same place. Failing to rotate means growers must use more pesticides, fungicides, and other chemicals with their associated economic and environmental costs. Rotation cuts these costs – sometimes to zero.

In addition, rotation has a lot of untapped potential. With the right design, tools, and timing, rotation can achieve all the goals mentioned above plus weed control – which is a major issue in organic vegetable production. A weed is simply a plant out of place. However, weeds can be a real challenge for home gardeners.

The rotation explained below is based on weed management. Before we get into the details of it, consider these pieces of essential information.

• When thinking about crop rotation, remember the garden beds stay put and the type of veggie moves each year.

• As far as mulch goes, hay is usually cheaper than straw, but it contains weed seeds. Straw is more expensive, but it is usually free of seeds.

• A fourth bed (and year) that is planted in a cover crop, such as clover, can easily be added to the rotation below.

• If your favorite vegetable does not appear in this rotation, think about its characteristics and slot it where most appropriate.

It is human nature to blossom at the possibility of building something new but to wilt at the thought of upkeep. People tend to love projects but hate maintenance. This system is designed with that in mind. After the initial design and installation, ongoing maintenance is kept to a minimum.

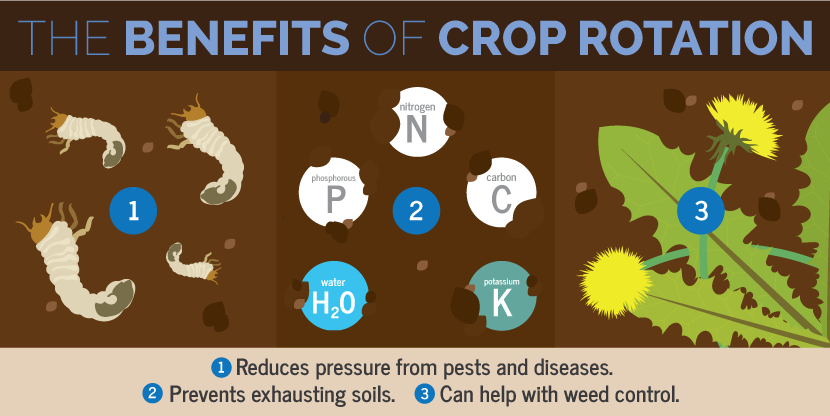

An Easy Three-Year Rotation

As noted above, the principle design strategy behind this rotation plan is weed management. With this in mind, the plants grown in each bed are selected for key characteristics that suit the management techniques for that particular bed. For example, tomatoes and onions tend to grow well when heavily mulched, while carrots and beets should be sown into a bed clear of mulch and weed seeds.

As implied, this rotation plan includes a mulched bed and an un-mulched bed; but what about the third bed? It is a transitional bed planted with vegetables whose form suits a regular schedule of light tilling. This will become perfectly clear as each bed is explained below. To keep things simple, the beds will be identified as Mulched, Transitional, and Weed-Free.

In organic garden management, we can’t expect to harvest food year after year without replacing fertility. While the generous use of compost is integral to this management plan, a cheap and easy way to maintain or even increase organic matter in soils is by mulching with straw or hay once every three years.

In addition to this essential aspect of organic gardening, the benefits of mulch include weed control and reduced soil evaporation. Once established, the mulched bed becomes nearly maintenance-free for the rest of the growing season.

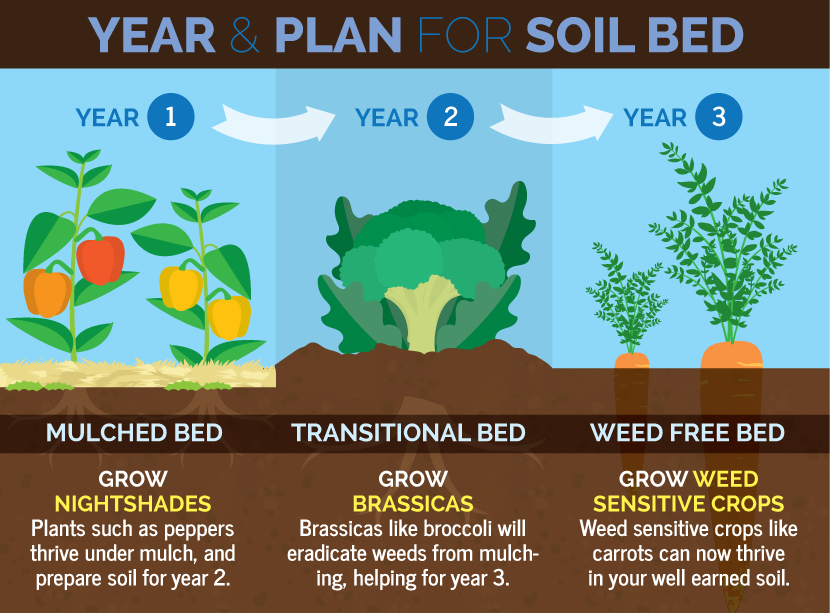

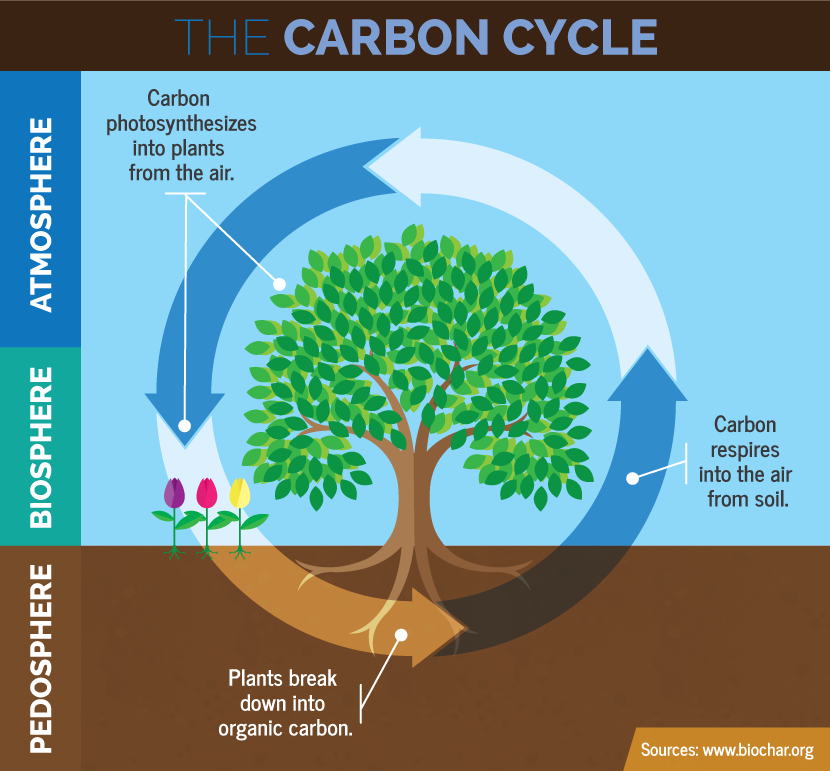

The graphic below shows the incredible natural happenings of the nutrient cycle. Understanding that nutrients are being exchanged back and forth between organisms, the atmosphere, and the soil, can allow us to address our gardens' needs differently. By skilfully rotating what is planted, we can keep our garden soil healthy by reducing the disparities in nutrient levels.

The selection of plants for this bed includes tomatoes and all the plants in their family, which are known as ‘nightshades’ or solanaceae. These include peppers (capsicum, chilis), eggplant (aubergine), and potatoes. Most varieties of tomatoes remain healthier in mulched beds because the mulch acts as a barrier between the leaves and the soil, which can harbor diseases.

Please note that some garden books advise gardeners not to plant tomatoes and potatoes close to one another because of the potential spread of diseases. However, from a crop rotation standpoint, it would be even worse to have one follow the other from one year to the next, and it is always better to keep plants of the same family together.

The other family chosen for this bed are the alliums, which include onions, garlic, and leeks. These veggies tend to grow much larger when soils are kept moist and without weed competition. Heavy mulch takes care of both.

Transitional Bed

The year after our nightshades and alliums have thrived in the mulched bed, the straw or hay has begun to break down and become humus. If hay was used instead of straw because of cost or availability, weed seeds will be abundant alongside any existing dormant seeds that were already in the soil.

The guiding principle for the Transitional Bed is to eradicate this ‘seed bank’ in the top ½ inch (1.5 cm) of soil while growing an abundant crop of broccoli, cauliflower, cabbages, and Brussels sprouts. These plants are in the brassica family, and they can be joined by other veggies that are shaped more or less like a tree: narrow at the bottom and wide at the top.

This tree-like form allows the easy and regular tilling of the soil surface to kill weeds as soon as they germinate. This entire bed is designed around the use of the most amazing of garden tools: the stirrup hoe. The thin, sharp, oscillating blade works by moving forward and backward (pushing and lulling) to skim the soil surface or just below.

The mantra for weed management in the Transitional Bed is, “Once a week on a sunny, windy day.” Using a stirrup hoe or similar tool, tiny weeds are easily uprooted and left to desiccate on the soil surface. After six to eight weeks, the seed bank will have been exhausted and further tilling is unnecessary. Using this technique, 99% of weeding can be done without bending over.

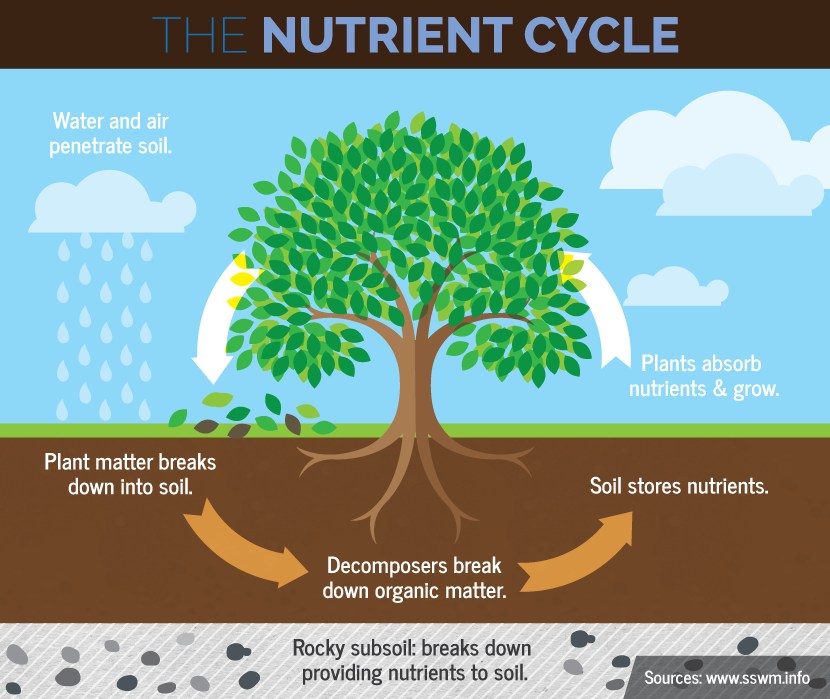

Like the nutrient cycle above, the carbon cycle shows the way that carbon is transferred between the atmosphere, the biosphere, and the soil. Thinking about how the environment trades carbon back and forth can help uncover the nature of the plants in your garden.

Your Weed-Free Bed

The year after our brassicas have thrived in the transitional bed, we are left with every gardener’s dream: a plot of earth with essentially no weed seeds. This is especially important when direct seeding carrots, beets, corn, or lettuce. There is nothing worse than spending hour upon hour hand-weeding a row of newly emerged seedlings. Because of the work done in the previous year, veggie sprouts can grow virtually uncontested.

If for any reason weeds do appear in this bed, a stirrup hoe can be used between the rows while reciting the mantra above. Once the plants in this bed have grown to three inches (7.5 cm), there is no reason that mulch cannot be applied to reduce evaporation if, for instance, it is a dry summer and you are going away on holiday. After all, this bed would be less than a year away from being completely re-mulched and planted back to nightshades and alliums.

Embed the article on your site