The Health Benefits of Friendship

In the 2000 adventure film “Castaway,” Tom Hanks plays a character shipwrecked on a deserted island who is so desperate for companionship he endows a volleyball with human qualities and relates to it as if it were his best friend.

Wardens of prisoner-of-war camps and penal institutions have long recognized solitary confinement or complete isolation from fellow inmates as one of the most painful, dreaded forms of punishment. Human beings are social animals, and it comes as no surprise that isolation from family, friends, and other members of your “tribe” has a powerful effect on mental health. But in recent years, a number of studies have shown having (or not having) friends has a powerful influence on physical health, as well.

As it turns out, having friends is not only good for your soul but it’s good for your body, too.

People with Friends May Live Longer

A 2010 meta-analysis of 148 different research studies found that “people with stronger social relationships had a 50 percent increased likelihood of survival than those with weaker social relationships.”

The somewhat fuzzy term “social relationships” doesn’t have a universally accepted definition, but for researchers in the social sciences, it encompasses friends as well as family members. It also includes belonging to a church or volunteer organization.

To grasp the full impact of these findings, consider the comparative role of other known risk factors on survival: social relationships have about the same influence on the odds of dying earlier as smoking and alcohol consumption, and even more than physical inactivity and obesity.

So while losing weight and eating healthy top the list for most popular New Year’s resolutions, consider including “make new friends” on the list.

Why Social Relationships Prolong Life

The two main theories behind the influence of social relationships on longevity are the stress buffering model and the main effects model. Neither one is better than the other at explaining this influence; to varying degrees, they are both true.

Stress Buffering Model

According to this model, the people in our lives are a source of useful information as well as emotional, practical, and, sometimes, financial support. These resources promote healthier behavior, but more importantly, they influence our bodies’ physiological responses to acute or chronic stress. The benefits of our social relationships thus “buffer” the harmful influences of stress. Supportive friends help us weather the frustration, pain, loss, and disappointment that are an inevitable part of life.

Main Effects Model

According to this model, when people belong to a social network, they typically conform to its norms concerning health and self-care. Direct encouragement by friends or modeling of healthy behavior motivates us to take better care of ourselves. Being part of a social network also lends greater meaning and a sense of purpose to our lives and increases our self-esteem. Through direct encouragement and the example of their own behaviors, healthy friends show us how to take better care of ourselves. And when we do, it boosts our self-esteem.

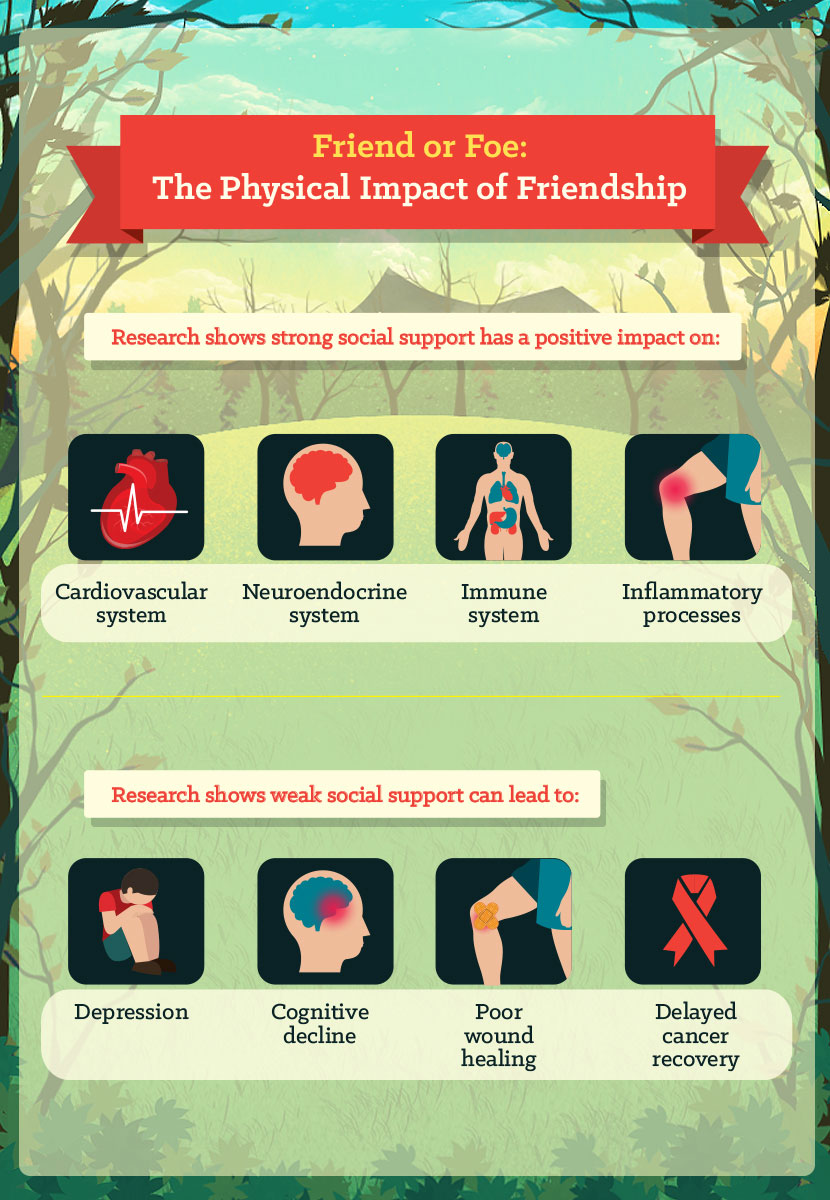

The Cardiovascular and Immune Systems

In recent years, more detailed research has identified which specific disorders and conditions are influenced by strong social relationships. The list is long. Having good friends and other social connections has an impact on a wide range of conditions, from heart health to cancer.

- A 2006 study found that strong social support has a positive impact on the cardiovascular and neuroendocrine systems, as well as the immune system and inflammatory processes implicated in poor health outcomes. Other studies have correlated a weak social network with depression, cognitive decline, poor wound healing, and delayed cancer recovery.

- Another study explored the influence of “negative emotions” (anger, envy, despair, etc.) on the entire immune system. Inflammation has been linked to cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, arthritis, type 2 diabetes, some forms of cancer, Alzheimer's disease, and even periodontal disease. And because the inflammatory response “can be directly stimulated by negative emotions and stressful experiences,” the study authors argued that close personal relationships that diminish negative emotions may enhance health “through their positive impact on immune and endocrine regulation.”

These studies lend support to the stress buffering model: the emotional resources supplied by friends and other social connections ease the stress of life and lessen its effect on our physiological processes and, in particular, our immune system.

Not All Friends are Created Equal

We’ve all heard about or known kids who get involved with the wrong crowd and begin to act out or go downhill academically. Maybe you know of people who belong to a social set that exerts a bad influence: its members may be heavily involved with drugs, addicted to the party life, or overly status conscious, for example. While a supportive network of healthy friends can be uplifting, surrounding yourself with slackers or partiers may only add to life’s stressors.

Because our social connections influence our health habits, it’s crucial to form the right kind of bonds. At their best, strong marital ties, supportive family relationships, religious affiliation, and close friendships have been shown to reduce stress and promote healthy behaviors.http://homes.chass.utoronto.ca/~siow/332/waite.pdfhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9813743 On the flip side, a bad marriage or toxic friendship may instead generate negative emotions and increase a person’s stress levels. As a result, a person with unstable relationships may stop exercising, eat less healthy foods, drink more alcohol, or resort to recreational drugs.

According to the main effects model, when members of a social set engage in unhealthy or self-destructive behaviors, they encourage others to do the same. Good friends are good for your health, but bad ones have the opposite effect. Remember that the quality of your social relationships is more important than the quantity.

Hundreds of Friends but Not a Single Confidant

By now, it’s a cliché: day by day, the world’s population grows ever more interconnected. The internet is shrinking our planet and making it increasingly “flat” (in the words of Tom Friedman) so that tragedies befalling foreigners in distant countries no longer seem quite so remote. Hashtags that express unity with suffering citizens across the world spontaneously spring up and go viral.

On the domestic front, Americans routinely have hundreds of Facebook “friends” and Twitter followers. Every day, we tell each other about vacations and parties and social events. We exchange our viewpoints with tweets and instant messages. It would seem people today know more about each other than ever before. But do we really?

While we may have some connection with a greater number of people than before, our social relationships tend to be less intimate and more superficial. In part, we can attribute this development to a culture that sometimes reduces communication to 140-character comments and encourages people to proclaim their triumphs (but not their disappointments) to the whole world. Neither one is conducive to true intimacy.

A true friend or confidant is someone who cares about more than having a good time, who is willing to listen when you’re in pain, and shares his or her own struggles from time to time. A true friend knows who you truly are. When people add a “like” to something you posted to your Facebook news feed, that doesn’t mean they actually care about you.

There’s something to be said for casual acquaintances, be they at church, the workplace, school, or around the neighborhood. Some social relationships go deeper than others, and not every one of them needs to be truly intimate. But we all need a close friend or confidant who will listen when we want to talk about more than last night’s game or what happened on “American Idol.” Social relationships of all types and degrees of closeness are important, but having at least one confidant is crucial.

Make Good Friends by Being One Yourself

Human beings form social relations because we need them. We’re tribal by nature, developing our sense of self through interconnection. Only through our personal relationships – as life partners, friends, family members, and parents – can we fully self-actualize. Hardy social relations are crucial for our emotional and physical health.

As a guide for developing the kind of social connections we all need by virtue of our genetic inheritance, consider relying on a version of the old golden rule: relate to prospective friends as you would like them to relate to you in return.

First become the kind of friend you would like to find and treat potential candidates for friendship with the interest and respect you hope to receive. Then pay attention. If your consideration isn’t reciprocated, this social relationship could be one that only increases negative feelings and adds to stress. That’s bad for emotional well being, of course, but it’s bad for physical health as well.

Embed the article on your site