An Ice Wine Primer:

Wine’s Frozen Delight

Imagine a wine that’s lower in alcohol, almost unbelievably pure in its concentrated fruit aromas,

sweet enough to be a treat on its own, but so refreshing that it doesn’t feel as though you’re drinking dessert.

That vision – Ice Wine – exists, and it might be one of the wine world’s most underappreciated delicacies.

Ice Wine is misunderstood (even by well-heeled wine snobs) primarily because it’s so rare, but also because it’s so confusing.

Is it Ice Wine, Icewine, Eiswein, or Iced Wine? The answer, in wine’s charmingly maddening way,

is “all of the above.” Don’t worry, we’re about to clear it all up for you.

Production Primer

First, it helps to know the common ground that all Ice Wine style wines share.

As its various names suggest, Ice Wine is made from frozen grapes.

The grapes used most often are those that handle the cold well, are quite aromatic, and keep their acidity when left on the vine longer:

Riesling, Vidal Blanc, and Seyval Blanc (for whites), and Cabernet Franc (for reds).

The best results usually come from grapes that are left to freeze while still on the vine, though many are made through cryoextraction.

During freezing, much of the water in the grapes becomes ice, and what’s left over are berries with ultra-concentrated juice, sugars, and acidity.

Those grapes generally must be harvested in the bitter cold at night, and pressed right away,

with very small concentrations of juice that is then fermented into wine, with much of the natural sugars remaining.

The result is a beverage that’s often slightly lower in alcohol than a dry wine,

much sweeter (as high as 300 grams of sugar/liter in some cases),

but with ample acidity (often over 10 grams of titratable acids/liter), which makes the wine feel refreshing and balanced in the mouth.

There’s both a literal and a figurative price to pay for the almost magically pure fresh fruit aromas and flavors, however.

Getting grapes to survive on the vine long enough to freeze means losing some grapes to diseases, pests, mold, bad weather, and hungry animals.

It also requires cooperation from Mother Nature, as the ambient temperature has to get low enough to freeze the grapes.

Harvesting and pressing the grapes is a painstaking process, and needs to be done in the bitter cold, at hours when few want to work, and in regions where labor and land don’t come cheap.

After all of that, yields are infamously small, special yeast strains are needed for the winemaking, and the fermentation process takes significantly longer than it does for dry wines.

Finally, you get a precious nectar of a wine that seems really pricey for a half-bottle – until you consider the labor of love required to make it.

The best way to get a deeper understanding of Ice Wine, next to drinking it of course, is to take a short tour of the wine regions that make the best stuff.

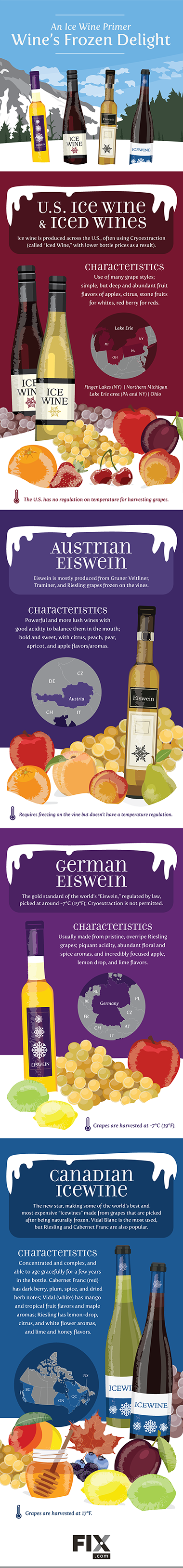

USA – Ice Wine, and Iced Wine

In keeping with the pioneering American spirit, several wine regions in the U.S. (including sunny California) produce ice wine,

though much of it is called “Iced Wine” as it is made from overripe grapes that are frozen using cryoextraction after harvest.

Typically, Riesling and Cabernet Franc are used, but it’s not uncommon to find producers experimenting with many other varieties such as

Gewurztraminer, Chardonnay, and even Cabernet Sauvignon. Cryoextraction usually translates into more affordable prices, but the wines still aren’t cheap, as the grapes are left on the vine for long periods of time, naturally reducing yields.

In some areas, such as the Finger Lakes region of New York state, temperatures sometimes get low enough to freeze the grapes on the vine, resulting in rare, delicious, traditionally made Ice Wines.

In general, Ice Wines made from white grapes in the U.S. are viscous, fruity, and aromatic, with white flower and stone fruit aromas, and apple and spice flavors.

Reds are chock full of fresh berry aromas and berry jam flavors. They are delicious and concentrated, with their complexity coming from the depth of fruit flavors.

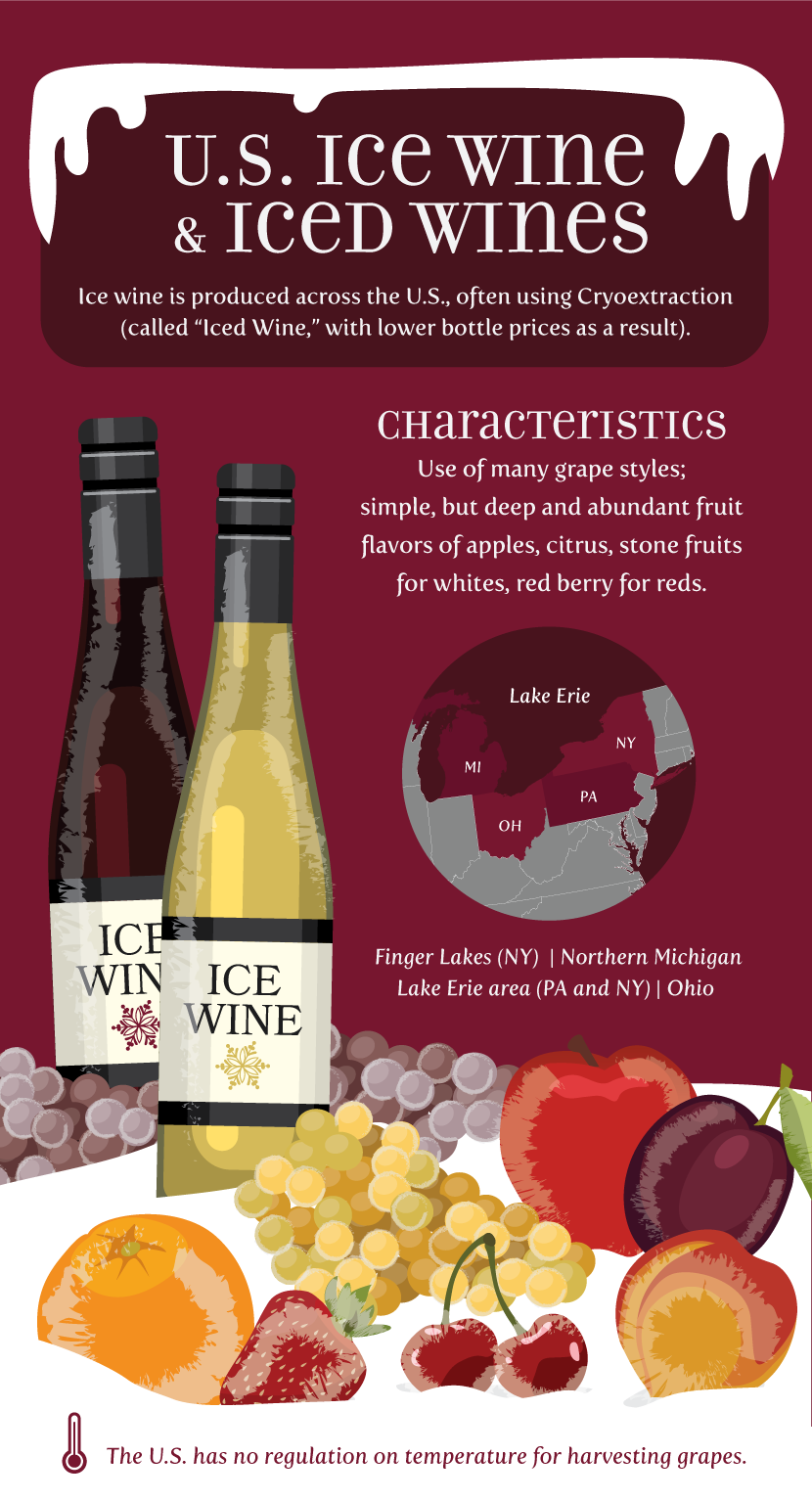

Austria – Powerful Eiswein

Austria is well-known for producing white wines that combine power with grace.

That description also holds true for the country’s Ice Wines, called Eiswein.

Most of Austria’s Eiswein is produced in the Burgenland region, where grapes are left to hang on the vine for extended periods after all other wine styles have been harvested.

Occasionally, the grapes (including Gruner Veltliner, Traminer, and Riesling) enjoy a long ripening curve,

with the final sugar amounts regulated by law, and then freeze on the vine, ready to be made into Eiswein.

Eiswein from Austria is bold, sweet, and racy, due to it ample acidity, and above all else, aims for purity of fruit (think citrus, peaches, pears, apricots, and apples, depending on the grape varieties used).

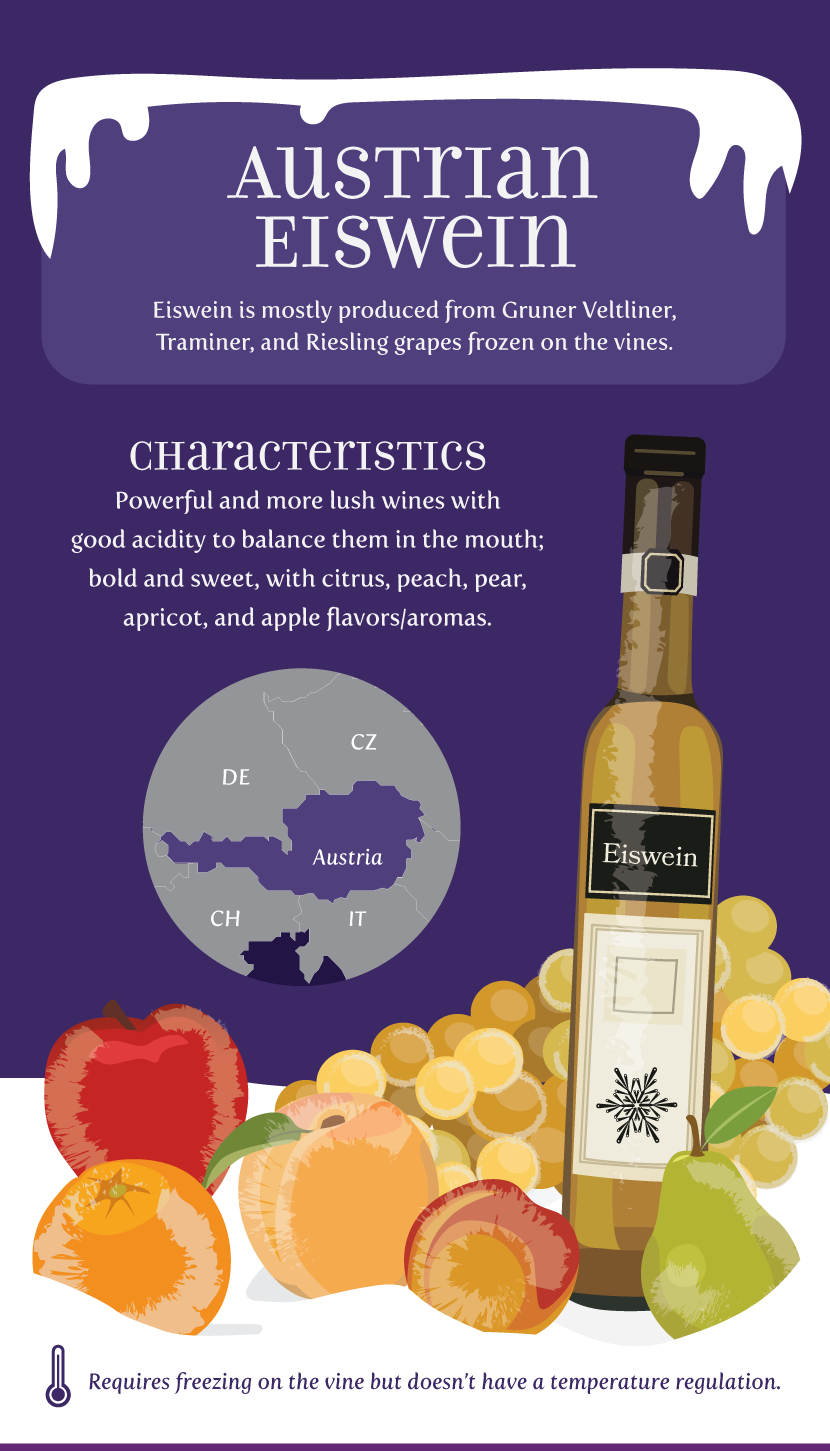

Germany – Europe’s Eiswein Star

Small quantities of Ice Wine are made all over northern Europe, including Denmark, Hungary, Croatia, Romania, Moldova, Slovenia, Switzerland, and Luxembourg.

The most famous producer is Germany, where Eiswein has long been a regulated quality category. German law even specifies the ripeness and frigid temperatures –

about 19 degrees F – at which Eiswein grapes can be harvested (cryoextraction is not permitted there).

In terms of grapes, Riesling is the undisputed star of Germany’s Eiswein show.

The main aim of German Eiswein is purity of fruit: the Germans produce Eiswein that is made only from naturally frozen, pristine, over-ripened grapes.

The result is usually like a fantastic German Riesling on steroids: piquant acidity, abundant floral and spice aromas, and incredibly focused apple, lemon drop, and lime flavors.

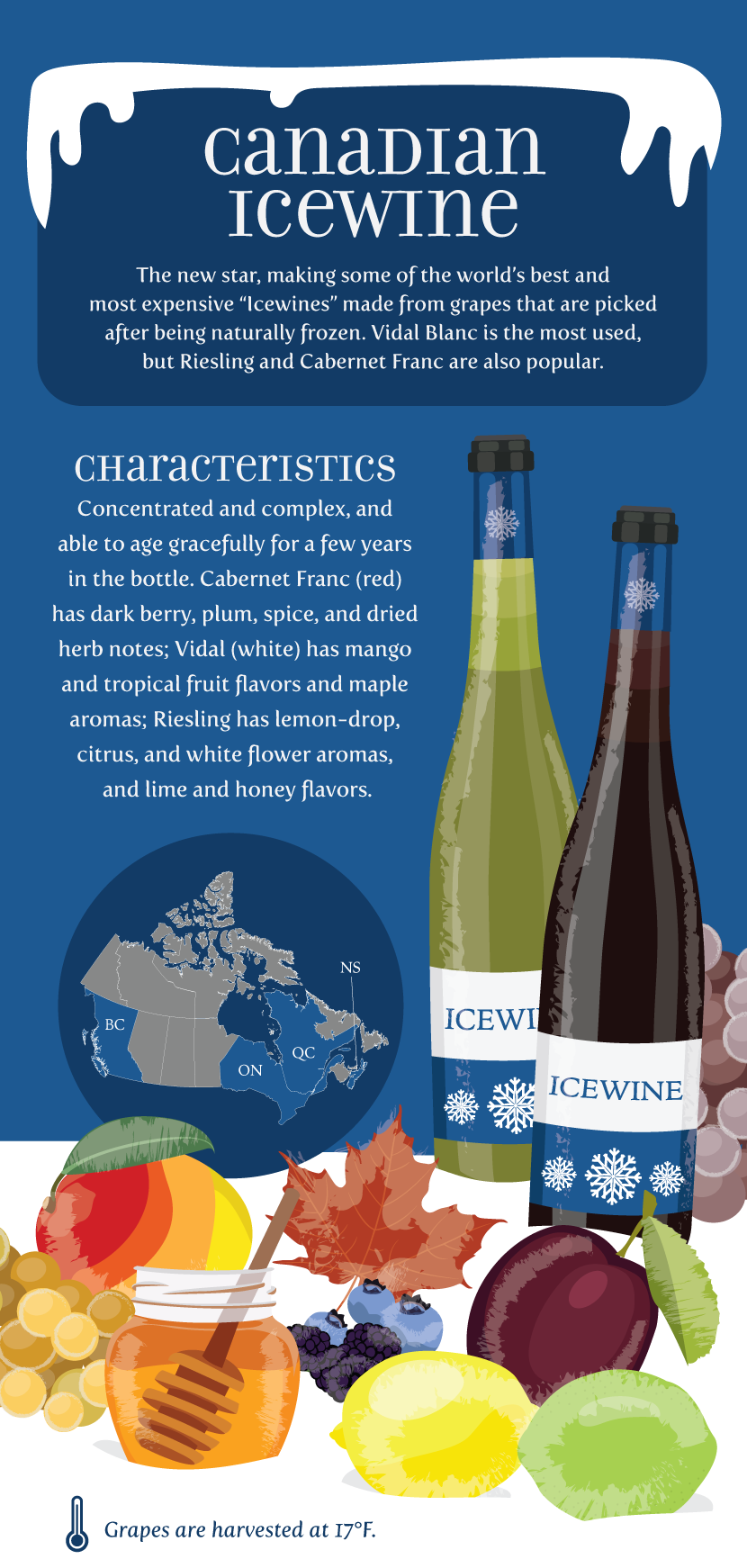

Canada – The New Icewine Star Up North

While Canada hasn’t been making Ice Wine (or, as it is known there, Icewine) as long as Germany has,

The Great White North is giving Europe’s best a serious run for their money in the battle for world Ice Wine supremacy.

Canada’s Icewines – usually made from Riesling, Vidal Blanc, or Cabernet Franc – are made traditionally,

with the grapes freezing on the vine, and are among the best and priciest Ice Wines offered anywhere on the planet.

Canada takes its Icewine very, very seriously, specifying the ripeness levels and temperatures (a bone-chilling -8 degrees C/17.6 degrees F) under which the frozen grapes can be harvested.

Much of the country’s Icewine production hails from the Niagara Peninsula, which enjoys the mitigating weather effects of having Lake Ontario nearby.

Generally, Canadian Icewine differs from the ice wines produced by its southern neighbor and by Europe by offering more depth, complexity, and powerful richness.

Vidal Icewines offer lush tropical fruits topped off with honey and maple aromas; Riesling Icewines emphasize the citrus and floral aromas, and age to produce honeyed flavors;

Cabernet Franc Icewines are deep, vibrant, and spicy, with dark berry and plum flavors.

Alas, production levels are low, and Canadians drink much of it, leaving only small and expensive amounts for the rest of us.

Regardless of where Ice Wine is made or how, it’s concentrated, lively, and unctuous.

Ice Wines usually present themselves best when served chilled, using small, tulip-shaped glasses to focus their powerful aromas.

The best time to serve Ice Wine is generally after a meal, offering it with dessert (fruit-based desserts are a particularly great match), or as dessert.

Embed the article on your site