Riding In Hot Weather

Keeping Cool On Your Bike

Being a year-round rider, I’ve encountered my fair share of both hot and cold weather conditions. Since riding with full protective gear, or ATGATT (all the gear all the time), is always the best option for safety, I have learned how to keep cool properly while riding in hot weather.

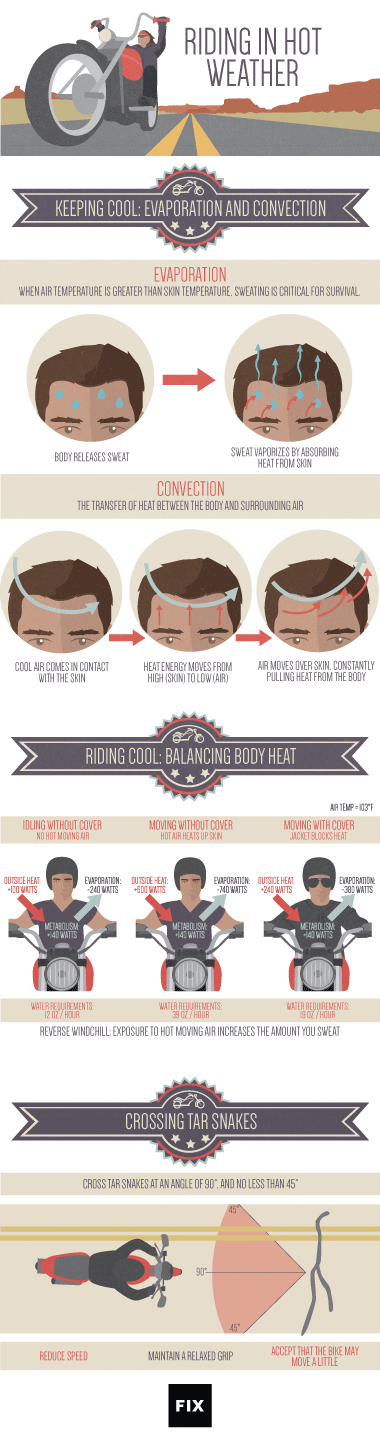

The Science of Sweat

Your body regulates heat by sweating. As sweat is released from the body onto the surface of your skin, evaporation occurs. Evaporation is the primary method by which sweat cools the body, and it works by the principle of “latent heat of vaporization.” Latent heat is the amount of heat absorbed or released when a substance, like water, changes state, such as from liquid to vapor. One gram or milliliter of water requires approximately 580 calories of energy to vaporize. This energy is drawn from the body in the form of heat. Thus, as sweat vaporizes, it pulls heat out of the body, cooling you down.

My riding jacket and pants are made of air mesh Kevlar, which vents well while still protecting me from the sun. But no matter how “vented” your riding gear is, you‘ll start to sweat when stopped for traffic lights and other obstacles. Once you get moving again, you‘ll be grateful for that sweat.

This can be explained through a process called convection. Convection is the transfer of energy by means of moving air that surrounds the body. When the air and the skin are at different temperatures, heat transfer occurs from the place of higher temperature toward the place of lower temperature. As heat is pulled from the body through evaporation via sweat, it warms the air directly around the skin. Wind pulls this air away from the skin, constantly replacing it with cooler air, thus constantly pulling heat from the surface of the skin. This is commonly known as wind chill. Unfortunately, when the air temperature is above 93°F, wind will actually heat up the body.

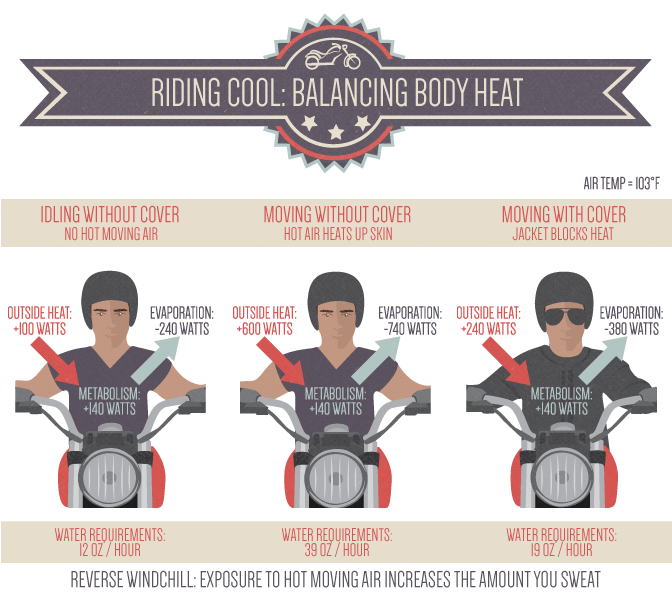

In a sort of reverse wind chill, when the air temperature is higher than the skin temperature, you will see the opposite effect. As you travel at high speeds in high heat, the amount of heat entering the body through convection drastically increases. One might think that wearing more clothes in such heat would be a bad idea, but the opposite is true. The amount of heat that has to be lost through evaporation, or sweat, also must increase.

Wearing wind-breaking material dramatically reduces the amount of heat inflicted on the body through convection, thus reducing the amount of heat that your body must lose through evaporation (sweating). The illustration below depicts three scenarios of sweating at high temperatures (103°F).

Tips for Riding Cool

In these high-heat conditions, I wear a long-sleeved, tight-fitting exercise shirt made of moisture-wicking material. I know that it seems counter-intuitive to wear long sleeves, but as long as you have air moving over the fabric, it will work great. Just think of the evaporation process described above. As sweat evaporates, it takes your body heat with it. Moisture-wicking material draws sweat away from the body to be evaporated through the shirt, aiding the cooling process. Conventional materials can simply trap sweat next to the skin, limiting evaporation. The key to these materials is air flow. If there is no air movement over the material, then the shirt will become oversaturated, and sweat will not evaporate.

When air temperatures are high and the reverse wind chill is in effect, wetting down clothing will increase the amount of moisture near the skin. This moisture is now available to be evaporated, drawing heat from your body. Although much of the evaporation will be caused by the high air temperature itself, there will be enough water on the skin to reduce the amount you need to sweat.

Some techniques for wetting down include neck bandanas (particularly those with water-absorbing crystals), wetting down a regular cotton t-shirt, or even pouring water directly into your helmet.

Keeping Hydrated

Now that we know how much water the body needs while riding in high temperatures, we can deduce that staying hydrated is one of the most important things to do while on the road. As covered in the above graphic, the difference between covering up or not is about 20 oz./hour and 40 oz./hour, respectively. Here are some tips to help ensure hydration.

Wear a Camelback: For longer rides, I wear a camelback-type water bag on my back. I usually fill mine with half ice and half water before the ride, and those cooling sips do add up to make the difference. If you‘re doing it right, you‘ll run out of water in the camelback before your next gas stop.

Carry Extra Water: I carry a gallon jug of water in my side case on longer days of riding. Be wary of taking in ice-cold water too fast. In my case, it causes an upset stomach. Swish it about your mouth to bring its temperature up a bit before swallowing.

Urine Test: Go for the clear. Dehydration is not something you can tough out – it will kill you if you don’t remedy it. Deep-colored urine and headaches are early signs that you are in need of water. If you stop sweating, heat stroke is not far behind. Drink water often!

Only Water is Water: Caffeine and alcohol are diuretics, which cause you to urinate and lose more water. When it’s hot, steer clear of sugary drinks, caffeine, and alcohol. Also, never drink alcohol directly before or during your ride.

Tar Snakes

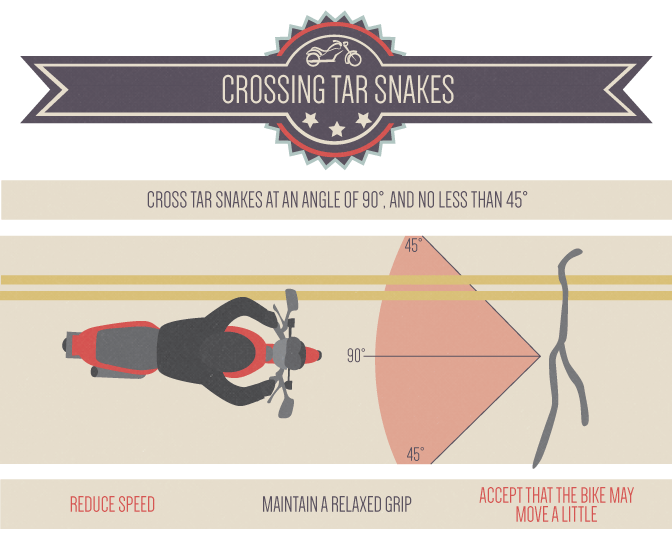

Tar snakes are a hazard for both motorized and pedaled two-wheeled vehicles and their riders. Many states use a tar-like material to fill in cracks on the roads; these can become quite slippery when it’s hot. Avoid them if possible. Treat them the same as railroad tracks by crossing them at 90 degrees and in an upright position. Slow down if your rear tire starts sliding out from under you – stay calm – and the tire will grip again. Don’t try to over-correct, keep your line, keep your head up, grip lightly, and keep your body steady for when the gripping action returns.

If there’s a large patch of tar snakes and there is no way to avoid them all, I will sometimes pull in the clutch and treat the obstacle as I would a large patch of ice, coast through it, and after ensuring that the rear wheel is clear, re-engage the engine. This helps to keep from slipping.

Riding in really hot weather is not bad when you’re prepared for it. Remember to hydrate, keep your skin covered, and avoid hazards. Don’t let the heat weaken you to the point where you’re not fully attentive to traffic conditions and the road. Basically, you must consider how your body will deal with the heat. Reducing the effects of convection, through covering up and wetting down, will reduce the amount of heat that your body must deal with through evaporation. Covering up in the heat will keep you cool.

Hot weather usually means lots of sun exposure, so get some good sunglasses or a darkened visor to prevent headaches caused by sun glare. And don’t forget to put sunblock on the back of your neck where your riding gear leaves the skin exposed.

Ride safe. Ride aware.

Embed the article on your site